The Haftarah Project: Sukkot (First Day)—Imagining Shared Redemption

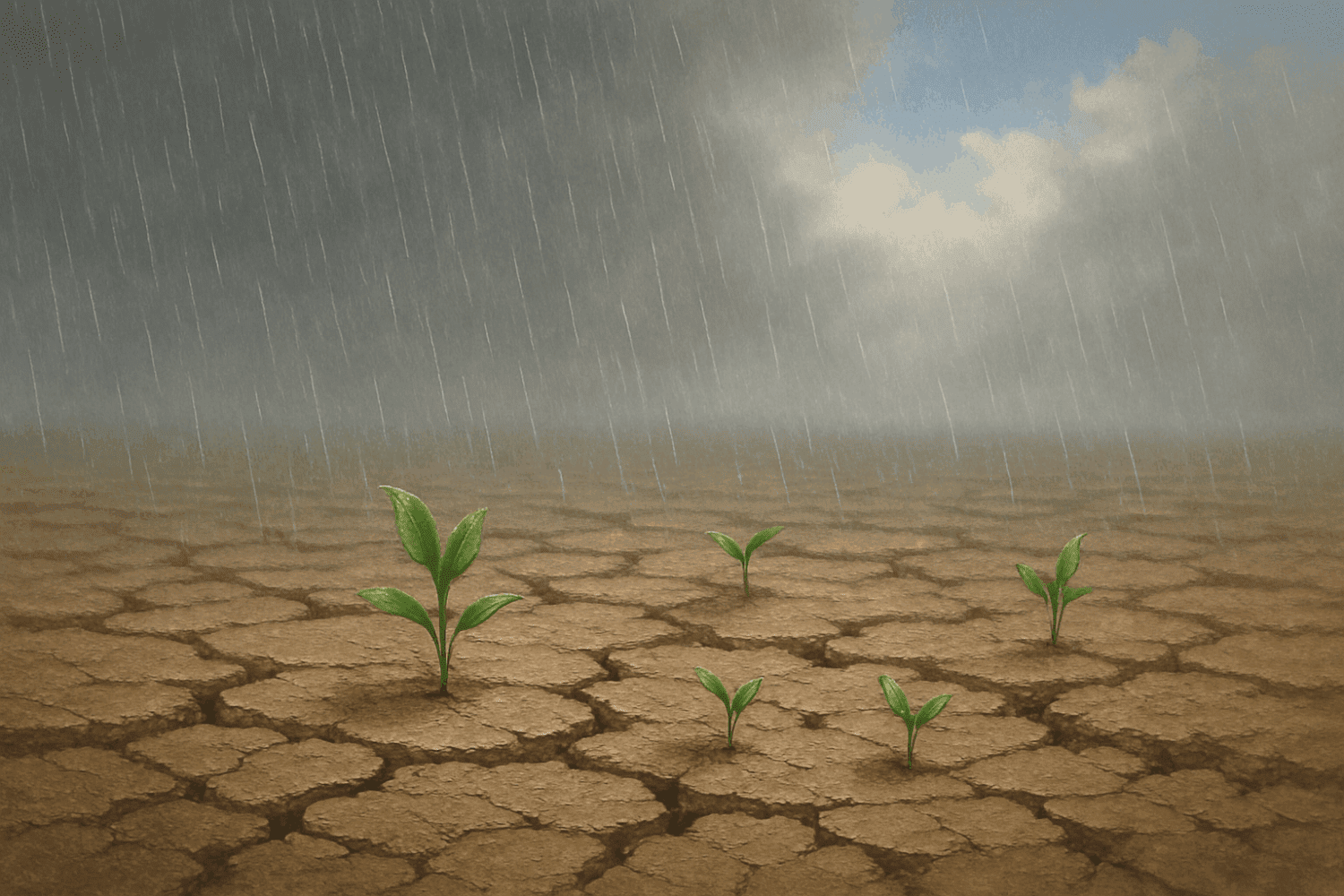

Image generated by Dall-E.

Reading the haftarah for the first day of Sukkot could easily lead to a case of emotional whiplash. Zekhariah’s prophecy (written after the destruction of the first temple, when the majority of the people were still in exile in Babylonia), alternates between images of war and destruction and images of a promised redemption. The nations of the world will besiege Jerusalem and most of its inhabitants will be exiled or uprooted, and then God will make war on those nations, split the mountains, and despoil the despoilers. There then follow images of a fantastical future of beauty and bounty, when water will flow from Jerusalem, there will be “a continuous day…of neither day nor night”; and God will be king over all the earth: “in that day there shall be one Lord with one name” (a phrase we might recognize from the Aleinu we say every day).

But that is still not the end. There is yet another promise of God making war on the peoples that have besieged Jerusalem, and smiting them with horrible plagues described in very graphic language; plagues that strike not only humans, but also horses, camels and all their animals. Whether because of the plague, or because of the fear the plagues engender, people will also battle with one another, “everyone shall raise his hand against everyone else’s hand.” The Israelites will gather in the wealth of those who have despoiled Jerusalem.

But after this battle, the haftarah ends with yet another image of paradise, when those of the nations of the world who survive the battles will make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to celebrate the holiday of Sukkot and pray for rain—and the rain will be plentiful when needed.

Two themes stand out here. One is the importance of water: water that will flow from Jerusalem and fertilize the whole area; and water that will come as rain in response to the Sukkot pilgrimage and give life to all those who depend upon it. This, apparently, is the reason this text was chosen as the haftarah for Sukkot, because at the end of this holiday week (on Shemini Atzeret), we say the prayer for rain. Water was clearly central to the lives of the Israelites at the time; and remains so today. I was reminded, reading these passages, of the battles over water that are taking place even now on the West Bank. Settlers intent on forcing Palestinian shepherds off their lands are doing everything they can to cut off or redirect the springs that are the water sources for their villages, and prevent them from having water for their families and herds. There has to be a way to share the water.

The second is the continued back and forth between destruction and redemption, a zero-sum game, in which there are winners and losers. The people of Israel, who are to be the ultimate winners, will face destruction and exile; but, ultimately, God will turn back to them (if they turn to God), and destroy all those who made trouble for Israel. In the end, the nations who recognize God as the ruler of all will be welcomed into Jerusalem and the future paradise. The redemption of Israel becomes the redemption of all the world.

Until recently, I think I mostly ignored the images of plague and Armageddon, focused on the redemptive vision. But as images of famine, plague, destruction, and escalating political violence fill our daily news feeds, it is hard not to attend to the violent Biblical imagery. Is war, in fact, the only answer?

Does it have to be like this? Can we not imagine other ways to bring about redemption? We desperately need to revive visions of plenty and to begin to imagine peoples’ living together in peace, both on that land and elsewhere.

Editor’s Note: The reflections from the Haftarah Project represent the thoughts and opinions of the author.