Sept. 14, 1865: Members and Seatholders

Fast Facts

-

BJ originally distinguished between two categories of congregants: members—who could vote on all synagogue issues, and seatholders—who paid an annual rent for their seat but had no say in the running of the synagogue.

-

Member dues and seatholder rental fees were the primary source of revenue throughout the nineteenth century.

-

In the 1840s, congregants could be fined for talking during prayers or failing to maintain proper decorum.

Over the first 100 years of B’nai Jeshurun, there were two categories of congregants: members and seat holders. Initially, becoming a member was somewhat like being admitted to an exclusive club. Applicants had to be recommended by current members and approved by the Board. Prior to the vote, a list of applicants would be posted in the synagogue’s vestibule for a period of 30 days. Prospective members also had to pledge to pay a given amount annually. Only members voted on policy issues. There were many fewer members than seatholders, with the latter having no say in the running of the synagogue.

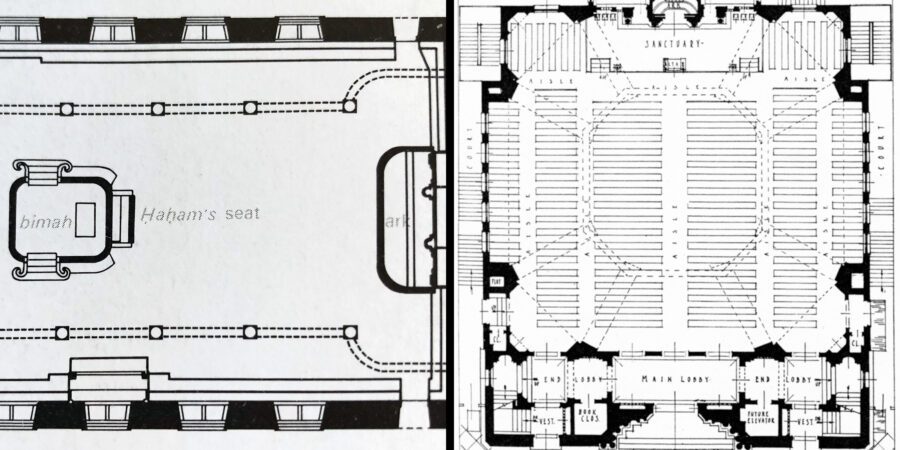

In the 1820s and 1830s, the income of the congregation was derived principally from a few sources: the sale of seats; fees charged at the admission of members; donations pledged during services; and the sale of mitzvot, i.e. synagogue honors. In the Elm Street building, seats were sold, usually by auction, prior to the High Holy Days. There were 350 men’s seats downstairs and 250 women’s seats in the balcony. The purchaser had use of the seats for the year. A number of free seats were set aside for the poor. In regard to mitzvot, the Trustees ruled “any person who may be called to the Torah shall offer not less than sixpence for one misheberech and three misheberechs for one shilling.”

In the 1840s, in search of greater decorum, it was proposed that the offering of mitzvot for sale be banned. Attempts at finding a dignified way of dealing with the issue continued for many years. Fines were also instituted to help establish proper decorum. Congregants could be fined for talking during prayers or for causing other disruptions during the service. Before Simhat Torah, if those assigned the honors of Hatan Torah and Hatan Bereshit declined, a fine was levied.

On September 14, 1865, consecration of the new, Romanesque-style 34th Street synagogue brought major changes. The new location and building helped generate a surge in the number of congregants. A different system was introduced for the sale of seats: they were divided into classes whose cost varied depending on location. Rather than being regarded as annual rentals, seats were now considered permanent purchases with fixed annual assessments. This helped to provide a regular income for the congregation. The 34th Street synagogue had 375 seats designated for men and 275 seats for women.

By 1920, the congregation’s principal sources of income were more diversified. Member dues and seat rentals continued, but added revenue now came from the sale of cemetery plots, donations for memorial windows and memorial inscriptions, and a portion of the Kol Nidre Appeal. As of 1925, the congregation was composed of 350 members with an additional 300 families as seatholders.

Source

Israel Goldstein, A Century of Judaism in New York: B’nai Jeshurun 1825–1925

BJ: The First 100 Years: 1825–1925

This essay was first published in an exhibition as part of BJ’s bicentennial celebrations.

Discover moments that defined BJ’s initial century: political protests, educational innovations, impassioned membership debates, and architectural milestones.