Jan. 1, 1901: Five Rabbis Across 20 Years

Fast Facts

-

At the start of the twentieth century, tensions continued to split reformers and traditionalists in the congregation.

-

Between 1901 and 1918, the congregation was led by five different rabbis.

The push-pull between reformers and traditionalists in the congregation began in the 1860s but was contained by Rabbi Morris Raphall, who insisted on mainly orthodox ritual. After Raphall’s death in 1868, the new rabbi, Henry Vidaver, agreed to incorporate some reforms. Rabbi Vidaver resigned by 1874, leaving the pulpit empty. In the absence of rabbinic leadership, the Board of Trustees decided to install an organ and allow mixed seating with “family pews.” The succeeding rabbi, Rev. Henry S. Jacobs, assumed the pulpit in 1876. He was described as a “conservative reformer,” and categorized as “conservative with reform tendencies.” The synagogue joined and then resigned from the Reform movement’s Union of American Hebrew Congregations during his tenure. Rabbi Jacobs was personally popular, and upon his death on September 12, 1893, he was eulogized as the “peacemaker.”

Following Rabbi Jacobs’ death, the synagogue’s recently appointed 21-year-old assistant rabbi, Stephen Wise, became the new full-time rabbi on January 15, 1894. He quickly became a sought-after speaker in synagogues around the city and involved in multiple boards of Jewish organizations. In 1899, Rabbi Wise was invited to lead Congregation Beth Israel of Portland, Oregon, and he tendered his resignation effective in June 1900.

As Rabbi Israel Goldstein describes:

For Congregation B’nai Jeshurun, the ministry of Stephen S. Wise was a period of intensive organization in the direction of education and philanthropy. The Sisterhood was organized, the Congregational Religious School and the Sisterhood Sabbath School were vitalized. The congregation as a whole was brought into contact with leading personalities and with leading movements and currents of thought. Very few of the organizations, however, survived. They were mostly, it seems, temporary responses to the stimulating personality of the leader.

Despite Rabbi Wise’s skills and persona, there was a notable apathy among the congregants at the Madison Avenue synagogue, with fewer regularly attending services or getting involved with its activities.

Between 1901 and 1918, the congregation was led by five different rabbis.

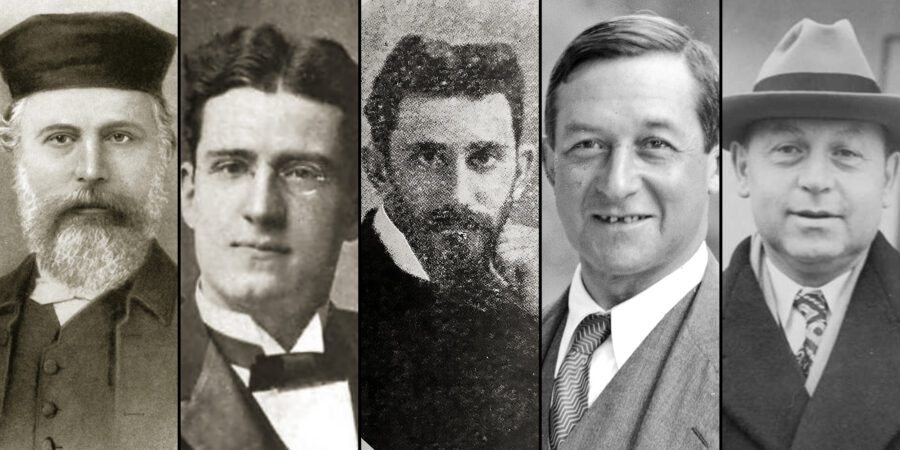

On January 1, 1901, a new British-born rabbi, Joseph Mayor Asher, took over the B’nai Jeshurun pulpit, with many leaders of the community expressing “high hopes.” Rabbi Asher was described as an orator of great power who aimed to lead the congregation back to a more traditional practice. He was appointed as a Professor of Homiletics at the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1902, and revitalized the religious school teaching of Hebrew. Despite his accomplishments, however, membership continued to decline. Disputes within the congregation about the use of English in the service intensified. In 1906, when Asher’s contract was up for renewal, he explained that “a fundamental incompatibility of religious viewpoints” made it impossible for him to continue. For a year, the congregation was once again without a rabbi.

In 1908, a young graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, Benjamin Tintner, became the congregation’s new rabbi. He attempted to reinvigorate the synagogue and—as many had requested—introduce more English into the service. It made no difference; attendance continued to decline. Rabbi Tintner resigned in 1910 following the Board’s refusal to renew his contract for more than one year.

The synagogue next turned to a more experienced, recognized leader, Reb. Dr. Judah Magnes. He was heralded as a leader in the counter-reform or neo-Orthodoxy movement. His views were not acceptable to his current congregants at Temple EmanuEl—and he refused to be a candidate for reelection there. He was then offered the pulpit at B’nai Jeshurun. At Dr. Magnes’s request, a special class of membership at the rate of $25 a year was established. Among other changes, the organ was silenced and the choir became male voices only. However, older members of the congregation were not happy with the changes, and there was no noticeable increase in membership. Before the end of his first year, Dr. Magnes indicated his desire to withdraw from the congregation to concentrate full-time on his many other activities. His resignation was accepted and he left exactly one year after arriving in 1912.

In 1913, the congregation hired Rabbi Joel Blau, who had a traditional background but also was a graduate of the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. Rabbi Blau described himself “as trying to occupy a position between Orthodoxy and Reform.” He came in on a wave of enthusiasm, but after four years the decline in membership and congregational involvement had not turned around, and his tenure ended in 1917. The Board planned for a move from the East Side to the West Side, where they hoped demographics would be more in their favor.

The rapid turnover of rabbis finally ended in 1918 with the installation of Rabbi Israel Goldstein, who would remain for over 40 years in the B’nai Jeshurun pulpit. During his tenure, Conservative movement affiliation was solidified and congregational membership and activities dramatically increased and revitalized.

Source

Israel Goldstein, A Century of Judaism in New York: B’nai Jeshurun 1825–1925

BJ: The First 100 Years: 1825–1925

This essay was first published in an exhibition as part of BJ’s bicentennial celebrations.

Discover moments that defined BJ’s initial century: political protests, educational innovations, impassioned membership debates, and architectural milestones.