April 15, 1829: The Evolution of the BJ Service

Fast Facts

-

From its earliest years, BJ continuously reformed its services to accommodate congregants and Americanize the service.

-

Over time, the service saw an increased use of English and music, as well as more sermons.

In 1839, Samuel M. Isaacs, a learned lay person, became the congregation’s hazzan and preacher. Though not an ordained rabbi, part of his responsibilities included regularly delivering sermons. Isaacs would actually earn the honor of the first person to deliver regular sermons in English in an Ashkenazic synagogue in America. He offered these teachings at designated times including Shabbat Shuvah (the Shabbat between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur), Shabbat Hagadol (the Shabbat before Passover), and on every Shabbat preceding the beginning of a new Hebrew month (Rosh Hodesh).

It was only during the 1850s, with the installation of the congregation’s first official rabbi, Rev. Dr. Morris Raphall, that Shabbat and holiday sermons in English became the norm.

In 1854, the first Kol Nidre appeal was made at the commencement of the holiday on behalf of a charity rather than the synagogue. It was not until 1879 that fundraising like this became a regular feature of Yom Kippur.

In 1855, one-third of the income of the synagogue derived from the sale of “mitzvoth,” or synagogue honors such as aliyot. But for the sake of decorum, many wished to end such sales, and in 1856, a compromise was reached that provided for the sale of “mitzvoth” to the highest bidder only for the High Holy Days, and not during the services.

In 1856, BJ organized the congregation’s first regular choir, consisting of 24 men and boys. This followed an earlier informal choir of eight boys and two men who had been drawn from the congregation’s Educational Institute (see the December 5, 1852, essay for more on this topic). Women were not allowed to join the choir until 1871. In 1875, the organ was added, further solidifying the role of music in the service.

In 1869, as was popular at the time, leadership added the new coming-of-age ceremony of Confirmation. This innovation mirrored similar rituals in Christian communities, where a person of about 16 years old would formally commit their allegiance to the Jewish community and tradition. Unlike a bar/bat mitzvah, confirmation was not an individual journey, but a cohort-based experience.

1856 was also when the synagogue’s hazzan started wearing a silk cloak and cap; in 1865, the wearing of a gown by the rabbi was instituted. In 1868, BJ changed the synagogue’s floor plan, moving the desk for reading the Torah from the center of the floor to in front of the ark. The same year, BJ Torah reading switched from an annual to a triennial cycle, and the introduction of family pews allowed husbands and wives to sit together for the first time. In 1870, a change was instituted whereby the hazzan and the Torah reader faced the congregation rather than the ark.

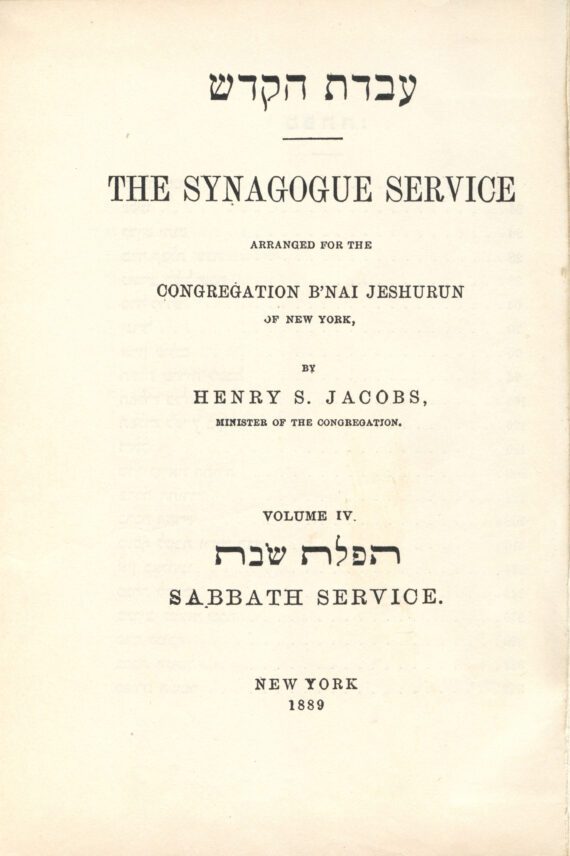

In 1889, BJ put out its own four-volume siddur, which included the substitution of English for a few traditional prayers and English translation on the pages opposite all the Hebrew prayers (though otherwise it mostly retained the Orthodox form). More English was introduced into the service over the period of 1907 to 1910 in an attempt to attract more congregants, particularly young people. In 1914, the decision was made to move the synagogue to its present location, which meant breaking the longstanding tradition of having the ark face east.

published by the congregation in 1899.

Source

Israel Goldstein: A Century of Judaism in New York: B’nai Jeshurun 1825-1925

BJ: The First 100 Years: 1825–1925

This essay was first published in an exhibition as part of BJ’s bicentennial celebrations.

Discover moments that defined BJ’s initial century: political protests, educational innovations, impassioned membership debates, and architectural milestones.