The Haftarah Project: Toledot—God’s Love Language

Image generated by Dall-E.

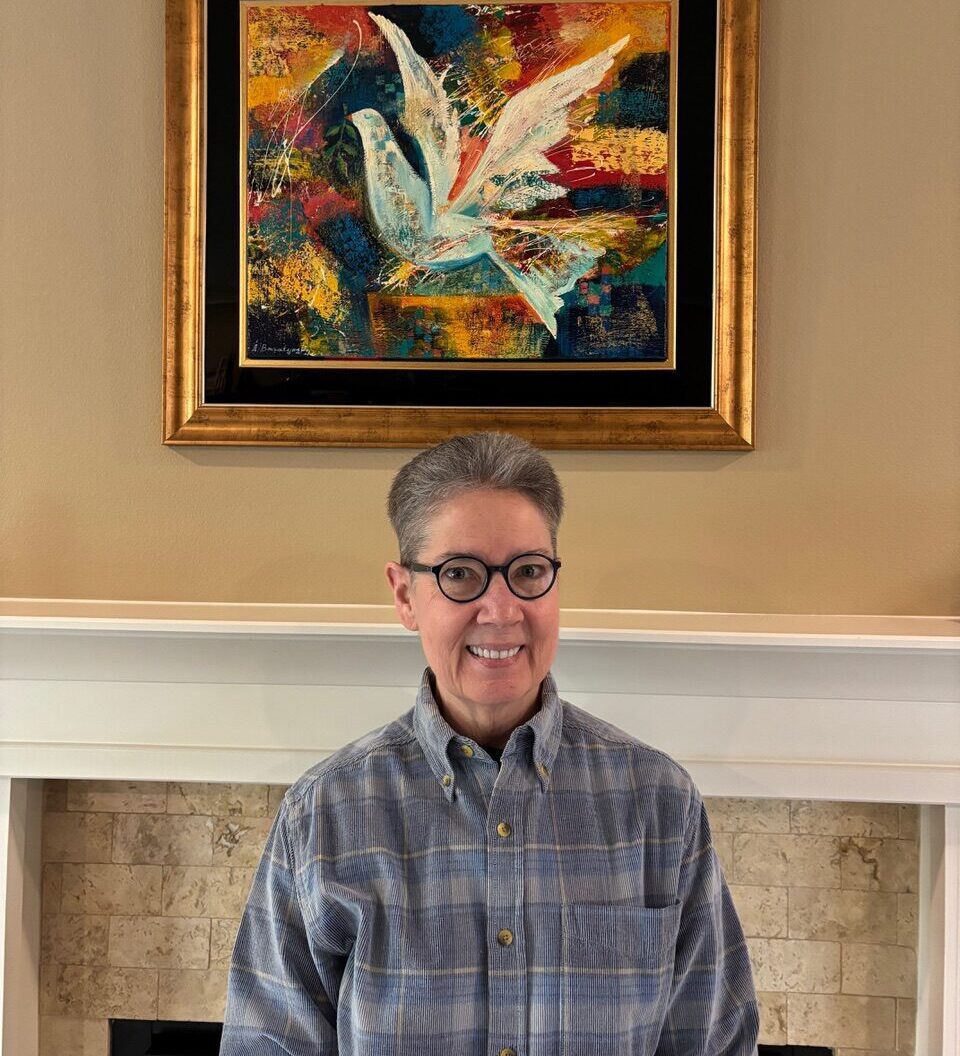

A major purpose of the Haftarah Project is to engage critically with texts that can be very disturbing to hear but that are rarely discussed by the Rabbis. It has become clear in the last months, however, that not everyone is equally comfortable criticizing biblical texts, especially their depictions of God. On a number of occasions, Rabbi Felicia Sol, Judith Plaskow, and Martha Ackelsberg–initiators of the Haftarah Project–have gone back and forth with contributors encouraging them to push harder against particular texts. Because Carmen is so articulate about what she is and is not willing to say and why, we thought it would be valuable to share some of our correspondence on Parashat Toledot to give readers a sense of how texts can be approached in many different ways. The conversation can be found at the end of her piece.

Shabbat Toledot—God’s Love Language

Emily, my wife of 38 years, is a vegan while I am a carnivore. Early in our relationship, Emily undertook the six-hour task of making my beloved grandmother’s (z’l) vegetable beef soup. She approached the process with some trepidation because besides the time involved, the recipe was vague. How long to cook the meat and onions before adding which vegetables, how much salt, how high the heat should be for each step—nothing was clear. I was no help on these details since I had never cooked the soup. There was nothing for it but trial and error. Even though Emily couldn’t appreciate the taste of Granny’s soup, nor even imagine why I loved it so, she kept at the process adding a little more of this, a little less of that. Today, Emily’s soup tastes just like Granny’s. But even the very first (less than perfect) pot was exquisite to me. Why? Because her effort said, louder than any words ever could, “I love you”. In the early 1990’s a popular book claimed that people have five primary “love languages”. According to the book, the key to a successful relationship is to love your partner in their preferred love language—not your own. If you fail to love your partner in their preferred language, your partner will not feel loved no matter what you do for them.

Could such a thing be true in our relationship with God? As we know, the metaphor of a romantic love relationship between God and Israel is common throughout the TaNaKh. In the Haftarah for Toledot (Malakhi 1:1–2:7) a mismatch in love language appears to be the situation. “‘I have shown you love,’ said the Lord. But you ask, ‘How have You shown us love?’”…“A son should honor his father… Now if I am a father, where is the honor due me?…said the Lord of Hosts to you, O priests who scorn my name. But you ask, ‘How have we scorned your name?’” And on the passage goes, accusation and response, neither seeming to understand the other.

As it turns out, the priests have been offering defective sacrifices brought by the people. Instead of offering their best, the people are bringing blind, lame, sick and even stolen animals. And by offering these, the priests are defiling the altar. God not only feels unloved but insulted. Crucially, God’s anger is directed at those who could do better but have chosen not to bring their best. “A curse on the cheat who has [an unblemished] male in his flock, but for his vow sacrifices a blemished animal…” What is going on here? It is not as though the Torah has been lax in describing exactly what and how a sacrifice is to be brought. The people cannot use the defense of a vague recipe! No, the problem is that the people and the priests have developed a lackadaisical attitude toward worshipping God. “When you present a blind animal … it doesn’t matter! When you present a lame or a sick one—it doesn’t matter! … You say, ‘Oh, what a bother!’ And so, you degrade it—said the Lord of Hosts.”

Although Malakhi is writing in the 5th century BCE and we (thankfully) no longer sacrifice animals as a way to draw close to God, his message remains relevant for us. “God asks for the heart”, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel notes repeatedly in his book, God in Search of Man. Going through the motions, even when “the motions” are technically unimpeachable, is not using God’s love language. God isn’t asking for perfection. But God is asking for our best. Does this mean it’s enough to just have good intentions? After all, Malakhi indicates that God is pleased with the offerings of “the nations”, even though it’s not likely they followed the Torah’s specifications.

Perhaps the answer depends on us. What are our capabilities? Are we giving our best? Do we run to do a mitzvah? Do we open our hand to those in need? Do we see the face of God in every human being? Do we honor all of creation? Do we support our holy community financially and with our time and talents? This is the love language that God asks of us. If we speak it, we may find, as in the beautiful words of Yehuda Halevi:

In my going out to meet You,

I found You coming toward me.

Conversation

Judith to Carmen:

Thank you so much for the d’var. It’s very beautiful. At the same time, an important part of the Haftarah Project is grappling with what’s difficult in the haftarot. So let’s say that Emily made you soup and it didn’t taste like your Granny’s. Maybe she skimped on ingredients because she thought the soup was extravagant. You then say to her, I’m going to turn your blessings into curses; I’m going to dump dung on your head; I’m going to abandon you. Isn’t that part of what’s going in this haftarah? What if you don’t just accept God’s point of view but ask: Who is God in this haftarah? What do you think? Is that too counter to your instinctive approach?

Carmen to Judith:

Unfortunately, I do think the approach you suggest is “too counter to my instinctive approach”. I did initially try to “argue” with the passage. But, honestly, I’m on God’s side in this one. If in fact Emily had purposely screwed up the soup (as opposed to making a mistake), she would not have been speaking my love language. And while I would not have responded by threatening curses—nevertheless, the blessings of a loving marriage likely would not have accrued. Nor would I have used the metaphor of throwing dung in her face! But—might I have withheld myself or reacted in a less than loving (in the sense of sacrificial) way? I don’t know. But I’ve sure seen it happen.

I guess a lot of it has to do with my concept of God. In short, I sense a reciprocal partnership albeit on a cosmic rather than individual level. I did try to write it differently. I had to keep throwing things away. I just couldn’t go there.

Judith to Carmen:

How do you see threats of violence fitting into a reciprocal relationship where the goal of the more powerful partner is in the end to elicit love?

Carmen to Judith:

Threats of violence—terrible, unacceptable, and–of course–ineffective! I guess I don’t see a real threat of violence here though. I’ve long thought of the “curses” language as mostly foretelling natural consequences of living outside of divine guidance. You can go astray, but a consequence will follow—not because some old man in the sky sends down a curse but because the world can’t sustain a selfish, greedy, cruel etc. way of life. As far as dung in the face—it’s such an outrageous idiom, it seems to me it can’t be taken literally. I think that kind of literal thinking is a trap.

I used to spend a lot of time at my Grandmother’s home. She took The Ladies Home Journal which had a regular column: “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” I was addicted to that column at 10 years of age! After the opening, you never thought the marriage could be saved. People did incredibly mean things to each other! But it was almost always out of pain. And they didn’t/couldn’t communicate that to one another. Amazingly, once the partners learned to communicate, the marriage did end up being saved (at least for the column). I think this and many other experiences have conditioned me to look beyond the words to the feelings behind them. Also, the major blame in this passage is on the priests. They are supposed to be examples and teachers for the people. It’s bad enough to not care yourself—but to lead an entire people astray? The entire endeavor would be lost.

But actual, real threats of violence—no, never acceptable.

Judith to Carmen:

The way you describe curses is exactly the way I read the second paragraph of the Shema. But there’s too much actual and metaphorical divine violence in the Torah and prophets for me to be able to explain it away. Of course, I don’t mean to say that that’s how I understand who God is, just that I feel I need to grapple with the way in which the character of God is portrayed in the text.

Felicia to Carmen:

I appreciate the idea of a reciprocal partnership and of course the power of the love language. I also appreciate that it may be hard to dig into the difficulty that we are assigning to the haftarah because of language at the end that is particularly harsh and some might say abusive. I think we are trying to wrestle with those painful images.

There seems to be a consistent element in God’s “love language” that feels unholy in some way. I understand the theological idea that with a selfish world comes implications even if God is not trying to move us around on the chess board. But what does it mean to have a punishing–potentially abusive–God? That’s what we are trying to wrestle with. Does that resonate in any way? Even if the curses never come to be, if God were a parent or spouse, would we be so accepting of this relationship and its taunting? I’m curious.

Carmen to Felicia:

As I think I mentioned to Judith, I tried to approach the piece from the angle of the nasty language but I hit a wall. I just don’t think that is the language of God. I think that is the language of humans projected onto God. My struggle is, “what is this 2,500-year-old text really trying to convey? How can it speak to me today?” I’m not sure it would be speaking to me if I believed that language of curses and dung and such belonged to God. But it did speak and I wrote what it said. Maybe I could change it—I’m not sure. But I don’t think it would be my voice. I think a big part of my struggle, living in the South in a very red state, is to keep from drowning in despair. I can’t bear to think of God as punishing and potentially abusive. But I sure think people can be. And they project that onto God with gusto. Having encountered a different God than these harsh words suggest, I cannot “unsee” Her. I am compelled to look below, above, and beyond human language to encounter a living God.

Editor’s Note: The reflections from the Haftarah Project represent the thoughts and opinions of the author.