The Haftarah Project: Balak—Holding Contradiction

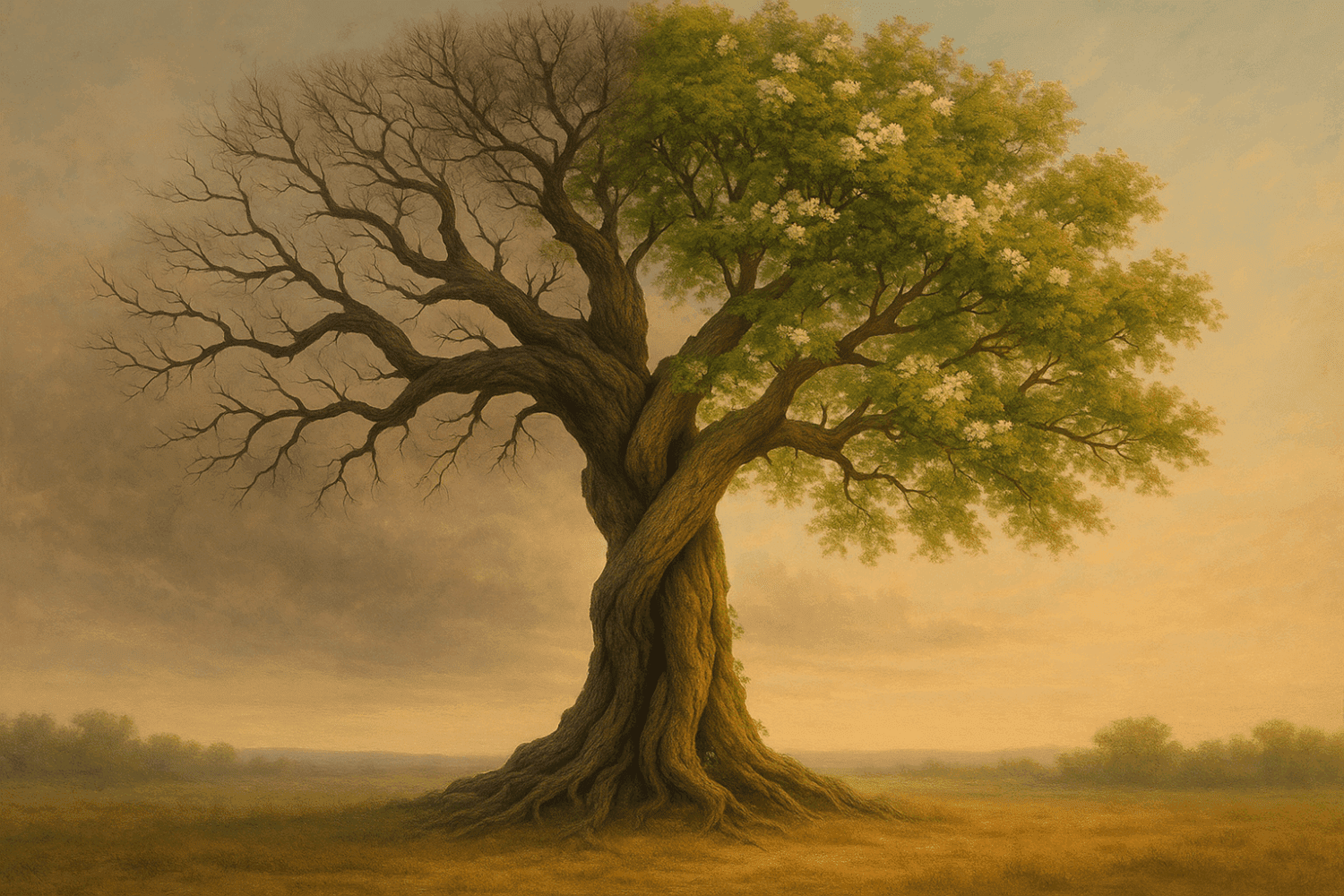

Image generated by Dall-E.

The haftarah from Micah for Parashat Balak is a particularly interesting example of a reading that contains a dizzying mix of disturbing and rich material. The haftarah begins with a vision of the restoration of a “remnant of Jacob,” probably after the Northern Kingdom was overrun and dispersed by Assyria in the 8th century BCE. It quickly morphs into threats of violence against Israel for engaging in forbidden religious rites: “I will destroy houses in your midst and wreck your chariots….I will destroy the sorcery you practice.…/ I will destroy your idols and the sacred pillars in your midst;…I will tear down the sacred posts in your midst” (5:9-13).

Divine rage is so central to many haftarot, and the invective against idolatry is such a familiar aspect of prophetic rhetoric—and such a standard and taken-for-granted theme in Jewish education—that it is difficult step back and fully appreciate what Micah and others are inveighing against. They are caricaturing and attacking religious practices that they consistently depict as foreign but that, on their own witness, are clearly being carried out by many within Israel.

The word translated as “post” here is “Asherot,” which may provide a clue as to what was at stake for those who worshipped other gods alongside YHVH. Asherah was the chief Goddess of the Canaanite pantheon, and it seems from repeated prophetic railing against setting up pillars and posts that she was part of Israel’s worship for a long period of its history. It’s not clear whether the term “Asherah” in the Bible refers to the Goddess or a carved wooden image set up in the ground, but the standard translation entirely obscures the connection to a female deity. Was there something particularly attractive to the Israelites about a female image balancing the male God? Do the prophets represent a minority voice—what one scholar has called the fringe “YHVH only” party—holding out against the continued worship of the female divine?

But at the same time Micah condemns female images, his teaching also contains a fascinating line elevating female leadership.

After describing God’s threats against the people for their disobedience, he turns to state God’s case against them. “What wrong have I done you?” God asks, listing some of the mighty deeds performed on behalf of Israel. “I sent before you Moses, Aaron and Miriam,” God says (6:4). This is an extraordinary statement, unique in the Tanakh. While Miriam was clearly an important figure in early Israelite history–she led the women in song at the Red Sea, joined Aaron in a challenge to Moses’ leadership (for which she alone is punished), and received a death notice in Numbers 20–this is the only place where she is listed alongside her brothers as an equal. It raises the intriguing question of whether there were other Miriam traditions that were edited out of the final biblical text.

Following God’s brief against Israel, the haftarah concludes somewhat unexpectedly with one of the most powerful and oft-quoted lines in the prophetic canon. What does God actually want in the way of worship, Micah asks? “You have been told, oh mortal, what is good, and what God requires of you: Only to do justice/ And to love goodness,/ And to walk modestly with your God” (6:8).

We are left with a question that might be asked of many haftarot: How do we navigate these clashing themes? How do we hold together the violence and intolerance with the insight and beauty? The text does not tell us how to express profound dissent with modesty rather than incandescent rage, but it functions both as mirror and caution as we deal with pain and anger at our own burning yet precious world. It has no interest in applying the call for justice and goodness to the desire for a female aspect of God, but it offers scattered clues as to the enduring nature of that desire and the contributions of women sidelined elsewhere. In the end, the complex and often-conflicting strands of our multifaceted tradition challenge us to explore for ourselves and as members of Jewish communities which parts we want to affirm, which we choose to grapple with and transform, and which we hope to leave behind.

Editors Note: The reflections from the Haftarah Project represent the thoughts and opinions of the author.